Social connection is a basic human nutrient just like food and water. There has been very little attention paid to this key determinant of health in neurological disease even though there is a robust literature on the dramatic impacts on health of loneliness and social isolation. Social isolation is as bad for your health as smoking half a pack of cigarettes a day or being obese. One key study reported the increased likelihood of death was 26% for reported loneliness, 29% for social isolation, and 32% for living alone. A review of the literature on social isolation in aging revealed a detrimental impact on depression, cardiovascular risk, and well-being. These issues can be very important for caregivers as well. We all need social connection. Veterans are particularly at risk for social isolation and loneliness as it can increase the risk of depression, anxiety, substance abuse and risk of suicide.

Parkinson’s Disease is a neurodegenerative disease that affects a diverse group of patients in terms of age range, race and gender, despite being historically thought of as a disease only affecting Caucasian older men. It has motor manifestations including stiffness and slowness, but also has a host of non-motor symptoms including constipation and blood pressure dis-regulation. Perhaps the most disabling symptoms come from mental health issues that are part and parcel of the disease. These include depression, anxiety, apathy, sleep, and cognitive issues that are very hard to treat. There are a number of proactive lifestyle choices that patients can make in their daily lives that may help modify the disease in a positive way. These include exercise, diet, sleep, mind-body approaches and social connection.

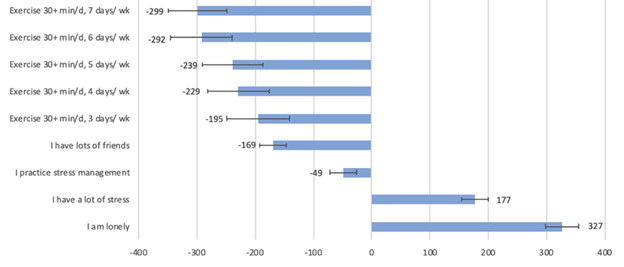

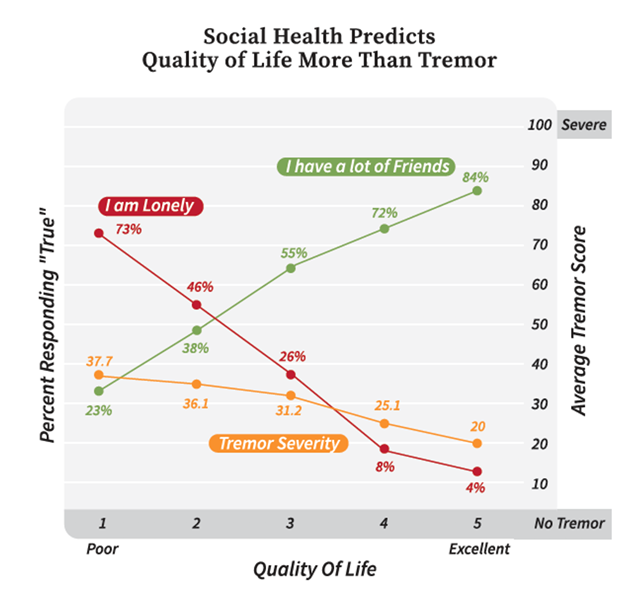

I along with Dr. Laurie Mischley and Josh Farahnik performed a study looking at a large cohort of People with Parkinson’s (PWP). The Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Parkinson’s Disease (CAM Care PD) study was designed to identify modifiable variables associated with the rate of patient-reported PD severity and progression. 1,527 participants with PD were available for this analysis. Individuals who responded “True” to the statement, “I am lonely” reported approximately 55% greater PD symptom severity over time. The higher the quality of life (QoL) score, the more likely the participant was to say they had a lot of friends or be partnered or married. The lower the QoL score, the more likely they were to report being lonely. Our study was a prospective, observational internet-based study that was designed to identify modifiable lifestyle variables associated with the accumulation of patient-reported symptoms over time. We found that being lonely is as bad for PWP as the beneficial effects of exercising 7 days a week for 30 minutes per day. Lonely PWP reported greater symptom severity for all 33 symptoms measured. Not unexpectedly, the greatest discrepancies between lonely and non-lonely individuals were found with social withdrawal, loss of interest, loss of motivation, loss of initiative, depression, and anxiety.

There are a multitude of reasons for social isolation in PWP and their caregivers. This can also happen in other neurological conditions as well due to issues such as stigma of the disease, difficulty with mobility, and inability to communicate. Some people may have embarrassment to go to restaurants because of drooling and difficulty handling utensils. Due to unpredictable bladder and bowel issues including incontinence, some may need to plan outings around their restroom breaks and consequently want to stay in the confines of their own homes. Difficulty commuting due to an inability to drive or ambulating for long distances is another limiting factor. This is especially troubling in climates with snow and rain. Apathy and depression can also contribute to further decreased motivation to frequent social functions or to engage actively while in attendance. Health care providers should become more proactive with screening for loneliness. Since there is a stigma associated with being lonely and patients may be averse to asking for help in this arena, specific screening questions should be developed. It has been noted that men have a harder time acknowledging that they are lonely and hence asking for help.

Researchers have identified three dimensions of loneliness reflecting the particular relationships that are missing. Intimate or emotional loneliness is the yearning for a close confidante or emotional partner. Relational or social loneliness is the longing for close friendships and social companionship. Collective loneliness is the need for a network or community of people who share one’s sense of purpose and interests. Loneliness can be felt if any one of these dimensions are not satisfied and hence, it is possible to be happily married and still feel lonely. Health care providers need to be vigilant about these spheres of loneliness so that they can seek and help treat patients who are at risk for getting lonely in any of these unmet arenas of social contact.

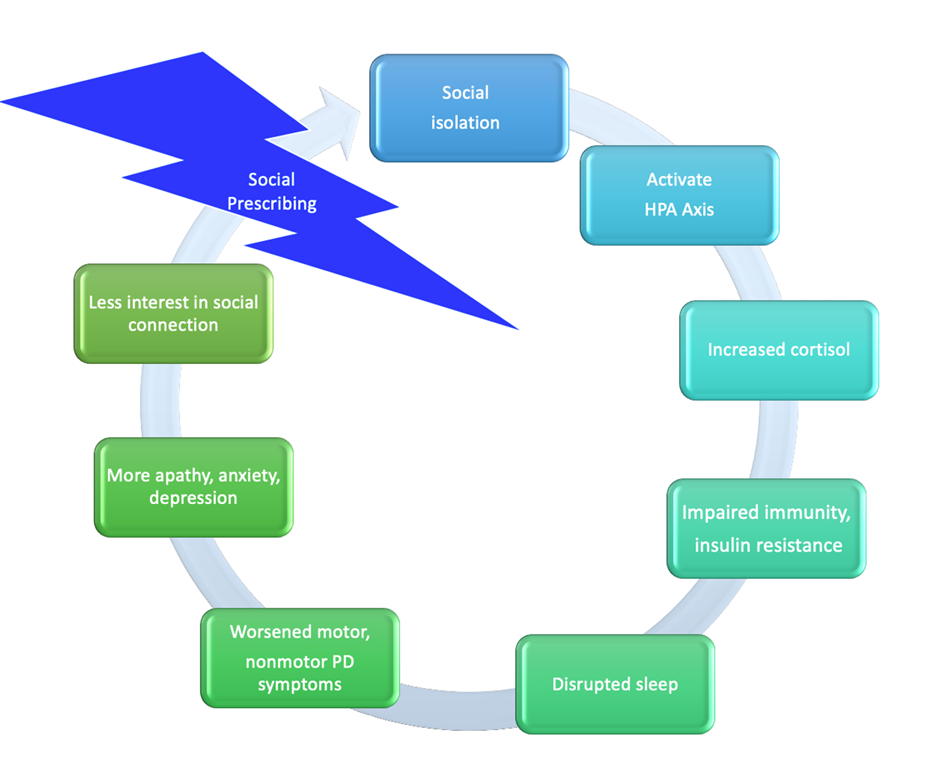

Social prescribing is a new concept in which clinicians recommend or prescribe resources or activities in the community to help patients develop healthy social connections. For example, the Togetherness Program at CareMore includes home visits, weekly phones calls, and connecting patients to existing social programs in the community. The Veteran’s Administration has recently created the “Compassionate Contact Corps Program,” using volunteers to call Veterans who are lonely and check in on them. Volunteering can help loneliness as well and so it has been proposed that Veterans be paired up with volunteers to make such calls. The National Health Service in the United Kingdom has designed a link social worker prescribing program that was recently highlighted in an article in the New England Journal of Medicine where they list referrals to group exercise classes, art-based therapies, volunteer opportunities, self-help groups for specific conditions, and community activities such as gardening, cooking and befriending as examples of social interventions.

We all need someone to confide in or a group of people in which to belong. Belonging to a support group, even a virtual support group using technology where patients can visualize one another on a screen or virtual exercise classes can be a critical source for human connection. A virtual happy hour or tea party may be helpful to keep patients connected. Proactive phone calls to patients from fellow patients, support group leaders, volunteers, or health care providers may be a critical link to the outside world for PWP who may lack a computer, smart phone, internet connection – due to cost or remoteness – or who may be technologically-challenged.

The pandemic of social isolation and loneliness is a mounting concern in our society today and there has been a call to action in highlighting this as a major public health concern akin to a pandemic. Compounded with the Parkinson pandemic, this call to action should be intensified. The synergistic COVID-19 pandemic with the need to socially distance, on top of these other two pandemics, may have the dire consequence of diminishing quality of life, social satisfaction, and exacerbating disease severity in individuals living with PWP.

We hope that PWP and their families will be proactive about staying socially connected despite the pandemic and reach out for help if they feel isolated or lonely. We are running a virtual support group through the PMD Alliance that is open to anyone who cares about PWP. All talks to date have been archived to Youtube for viewing later as well. For more information, click here.

Social connection is a universal human need. We urge you to pick up the phone and reach out to someone who may have been forgotten and may be lonely or socially disconnected. It could be the only human contact that the person may have had in a long time and could make a world of difference.